Roey Heifetz moved from Israel to Berlin as a young male artist in search of a future, and returned five years later as a mature female artist. This gender, but implicitly also geographical transition is at the center of her exhibition, Victoria, curated by Timna Seligman. The exhibition, currently shown at the Ticho House in Jerusalem as part of the Sixth Biennale for Drawing in Israel, includes a series of twelve large-sized drawings that enclose the small exhibition space from all directions.

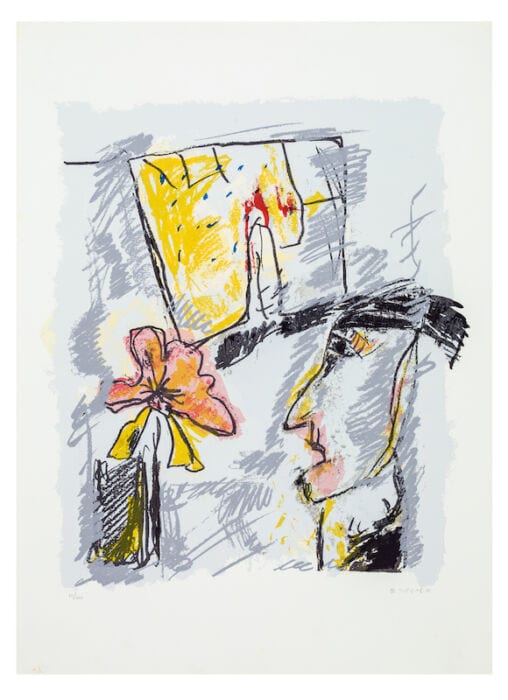

Heifetz draws aging transgenders. Her portraits are partly based on human figures she has met in Berlin as well as on her own, which is undergoing transformation. The figures are standing or lying down in stretched-out poses reminiscent of dancers’ and look straight at the viewer. Sometimes, their body bends, doubles or swivels, their hairstyles blown out and meticulously finished, and in some drawings, they seem like a genie out of a bottle.

Victoria is a transition exhibition. It deals not with the specific identity category, but rather with the disruption of the categorizing and pigeonholing order. It moves back and forth between what is identified as masculine and feminine, pretty and ugly, profane and pure, without pausing or committing to one identity or the other. The detailed drawing does not spare the body. It highlights every mole, wrinkle and out-of-place hair. Similarly, the painted transgenders move not only across genders, but also between the body image of a diva that is cultivated to perfection and never grows old, and the real body, withered and weary, which cannot overcome time. The result is an exhibition about lack or longing – a yearning for unity coupled with acknowledgement of the impossibility of realizing it absolutely and hence also action within that framework which truly is the absolute and permanent otherness.

Roey Heifetz – View of the installation. Photo: The Israel Museum, Jerusalem by Elie Posner

All that could have made for a critical statement and a gendered proposition, but these do not always suffice to produce a persuasive work of art. What makes the exhibition a success is its condensed expressiveness, evident in the raw materials, the drawing acts and the positioning of the pieces: the sheets of papers hang exposed with their lower margins rolling on the floor at the viewers’ feet. The nightmare of restorers and museum guards materializes in images of women that skyrocket to a height of 2-3 meters but swoop down to the squalid ground of reality that literally wallows is dust. The works could have naturally been protected by glass frames, but this would have produced different works that would have lacked the sense of fragile vulnerability that is so essential to them. Hanging this way, their skin and nerves are exposed by a proximity-compelling installation that combines compassion with mercilessness.

That same combination is also articulated by the intensive and hair-thin detailed graphite hatchings and by the lacquer stains and pigment powders that cover the images, tainting the surface and sabotaging the paper. Excessively elongated legs, forbidden hairs poking out of the toe joint, exaggerated eyeshades, potato-shaped chins and noses, creases that turn faces into bags of skin, large bright eyes gazing directly at the viewer, yellowish-translucent liquid stains and fur coats drawn in rust powder, wrapping the women and at the same time biting at their bodies.

Roey Heifetz, “Das Kannst du knicken”. Photo by Joachim Schultz

Heifetz notes the influence of well-known German draftsmen, above all grotesque expressionists Otto Dix and George Grosz. However, in Dix and Grosz’s works grotesqueness has a context – the city, club, military, etc. The drama in their works is also facilitated by contrasts and circumstances – the emaciated boy vis-à-vis the plump cigar-smoking industrialists, the soldiers and gas masks in the battlefield. In Heifetz’s drawings, there is no environment. The figures are all alone, and the drama is drawn exclusively in their bodies and facial features. Despite the broad white margins of the sheets, space is breathless and it feels as if the air is running out.

This isolation has particular significance: although transgenders are at the center of the exhibition, and despite the known fact that the works accompany Heifetz herself on the way to becoming a woman, this is not an exhibition about gender and society, identity politics, liberation and sexuality. Even if such aspects do appear in the works, their focus is existential and internal. They have something of the “thirst felt by every man with a soul”, as described by Rabbi Hillel Zeitlin in his essay “On the Boundary between Two Worlds”. Not a thirst “for something that has a beginning and an end, something inherently encompassed and enclosed”, but for what “lies beyond all boundaries”.

In fact, this is an exhibition about anxiety – the anxiety of age, loss, the transition into the unknown, the compulsion to move and the impossibility of return, the larger-than-life image faced by the slowly aging body, the fear of being like “people who sleep off their days”* – as opposed to the fear of jumping into the depth of self-discovery and the limbo of a search for meaning committed to an ongoing search that may never be satisfied. Layers of lacquer, powder and pigment, lines upon lines of intensive, unsettling drawing, have lacerated the gallery with pain, obsession and passion.

Roey Heifetz, Victoria

Curator: Timna Seligman

Ticho House, Jerusalem, Sixth Biennale for Drawing in Israel

Translation: Ami Asher

* Likutei Moharan – The essence of Rebbe Nachman's Teachings, 60.